The Prospect of a Mountain

Last year in November, a friend suggested that we go skiing together that coming January. I hadn’t really skied before, unless you count the three days I spent at the local dry slope as part of a school trip, when I was fourteen.

A few weeks later in mid-December, I was picking out Christmas cards to send hurtling out of London, to the family homes of a couple of friends. The card with an illustration of dogs driving home for Christmas, with a tree tied atop their car, to a friend with two dogs. A nativity scene for old family friends. Then, of course, a skiing scene for the friend that suggested the ski trip. Merry Christmas. Happy New year. January rolls around.

It’s always difficult going back to work in January, after some time off, even if this year we had the luck of the calendar and a public holiday fell on the would-be first day back. A Tuesday start to the working year. A couple of days later, in the evening, still in that first working week, I found my phone with a number of missed calls. I phoned back. We spoke about our Christmases, about the crippling first week back at work, and he mentioned the Christmas card with the skiing scene. Then he specified which dates to take off work, which flights to book and exactly which essentials I would need.

Three weeks later we were at the bottom of the Austrian mountain, getting our skis for the following day.

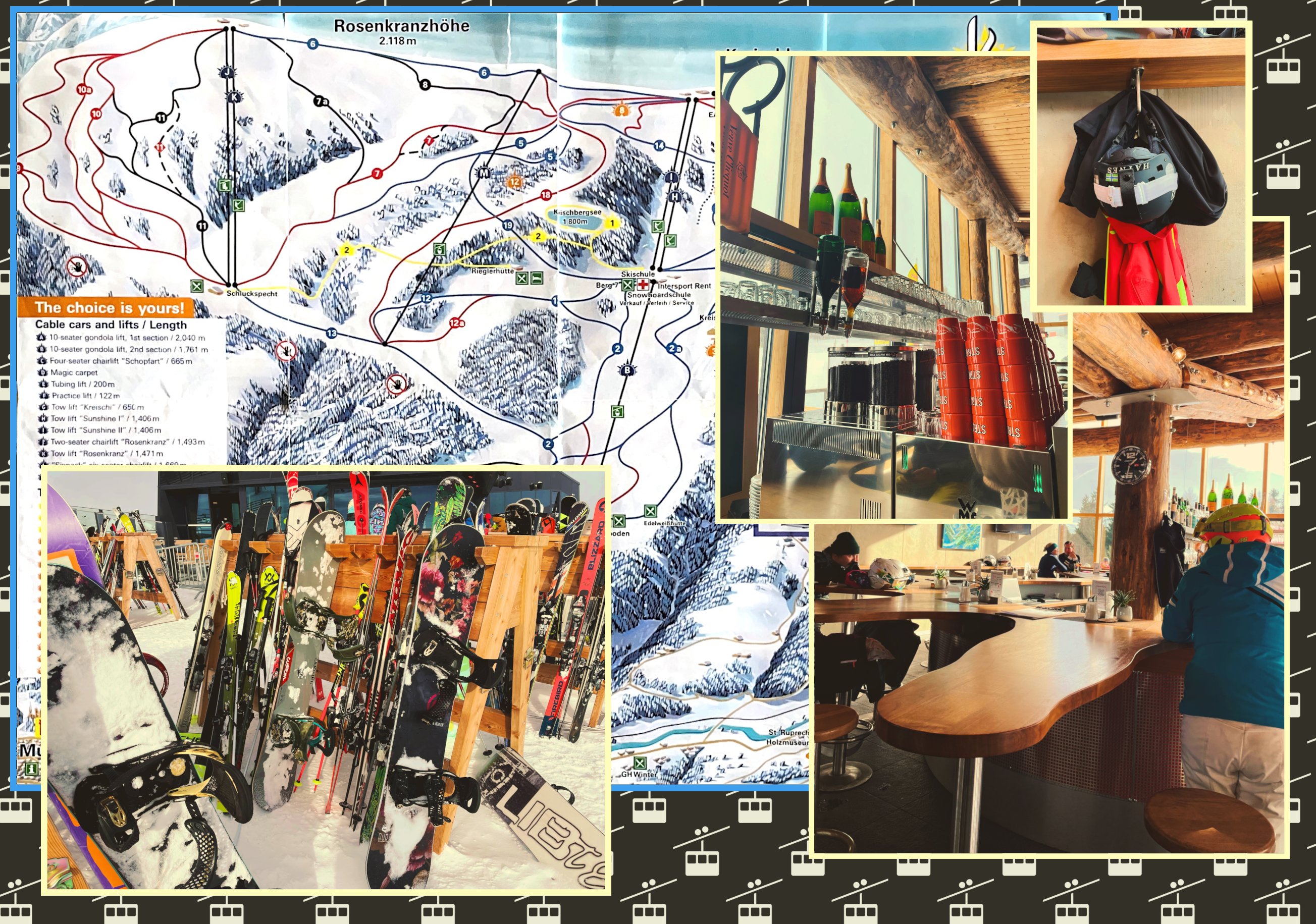

That first morning I had two hours in ski school with one of the others from our group, so we could find our feet. We threw our skis into the racks and caught the ten-person gondola halfway up the mountain. Stepping out of the gondola, my ski boots felt like morse code clickers, pounding down to start a message. We grabbed our skis out of the racks and walked out of the gondola terminal. With all of the equipment on, I was juggernaut like. I now saw the world in the orange hue of my borrowed goggles and the resolution of what I could grab between my gloved fingers felt large and obtuse. With the weight of the boots and the padding of the jacket and salopettes, my movements felt dampened. Like only some fraction of the effort I was putting into walking was being translated into movement. I felt tightly held in but not at all elegant. We found our teacher and it was time to clip our skis on.

I was clunky on the snow, my skis were like cat’s claws scratching the mountain and I could feel the weight of their length as I hopscotched around on the flats.

We skied down a forest run, past fir, larch and pine. Instructed to follow our instructor’s tracks, things started to feel a bit more natural and for the first time, I looked further ahead than five metres and realised that to descend, to speed up, was effortless. Down a mountain you keep going if you don’t do anything about it. We controlled our speed by inscribing large sinusoidal waves down the side of the mountain. Simple, harmonic, motion.

For Christina, our teacher, the mountain was undemanding. She would slowly look behind her and then as if by defying the gravitational laws would spin on her skis, now facing us, facing up the mountain, but going down, going backwards. She’d inspect the carved paths, and when we’d stray from her tracks, creating sinusoids of our own, bifurcating, we’d be given advice on how to balance our torso above our legs, when to bend our knees, where to turn, and how to dance on snow. After two hours, our time with Christina had come to an end and she skied on, into the windy distance, and almost as if one orchestral movement had ended and another was picking up, our man, who had predicted we’d finish up around this time and at around this piste, snitched past us and stopped a short distance ahead where we also came to a snow ploughing stop. It was time, in a wooden mountain café, for a break.

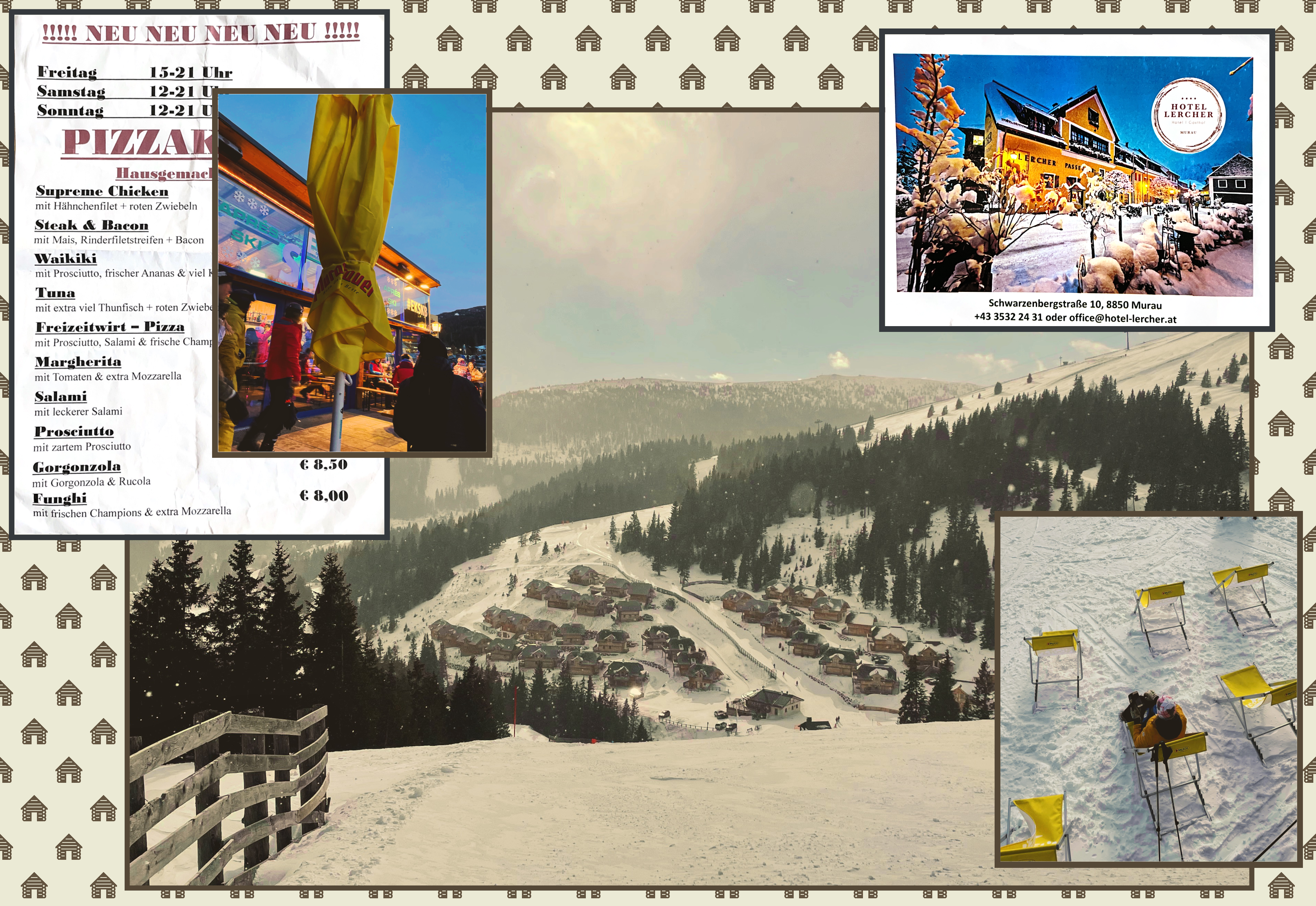

It felt ritualistic. Skiing, in the cold, stopping, unclipping the skis, throwing them up against a ski rack, going in, into this café, pulling off a layer, pulling off another maybe, ordering an espresso and pretzel, some soup maybe. It always came with a glass of cold water, the glass sweating, a release. So we perch up by the café bar, against the big windows, looking out onto the piste.

For a couple more days, we skied, paying homage to the café ritual once or twice a day. On our last day, we’re forced to make the hour drive to the next closest mountain after a snowstorm shuts all the lifts at the home resort. Half a day’s skiing is on the cards. We clip our skis on and make a few runs. When you’re on the ground, you feel encumbered, everything you’re wearing weighs you down. The soft orange of all the surroundings feels unnatural, artificial, edited. The helmet feels clumsy and your head as a whole feels top-heavy, the ski boots feel constricting, and it’s as if you’ve ended up on stilts. But when you’re going down the mountain, you feel light, protected against the elements, everything you’re wearing has its purpose and it all comes together in a kinetic rhapsody. The storm started to clear and the alps opened up to our west. The last couple of runs became a pursuit for parallel turns. It was icy as hell. The scrape of the sharp ski edge against the mountain added a timbre to the descent as we followed the contour of the piste one last time.